Research HighlightsMedieval Western Philosophy and Modern EpistemologyProf. Yoshinori UeedaDivision of Philosophy, Department of Philosophy and EthicsApr. 1, 2020

I have two main research themes: one that involves the history of Western philosophy and another that focuses on a particular field of modern philosophy.

My first research theme is Thomas Aquinas, whom you may remember from your high school history lessons. He lived in 13th-century Italy, where he wrote the Theological Summa and made important contributions to Christianity, particularly Roman Catholic thought. I want to take a philosophical perspective and understand Aquinas' ideas as consistently as I can from that standpoint. There could be many possible interpretations of what this type of Christian theology, which is commonly called scholastic philosophy, was. One interpretation is that scholastic philosophy was an attempt to make religious things manageable by using human reason to its limits.

As his framework for human reason, Thomas Aquinas used the philosophy developed by Aristotle in ancient Greece. Around the time of Thomas's life, the full body of Aristotelian thought was percolating into Europe via the Islamic world. This had a massive impact, including on Thomas, who devoted himself to the study of Aristotle's writings and wrote huge commentaries of them. He also took the astounding and bold step of using Aristotle's ideas to explain profoundly religious and mysterious concepts such as the Trinity and the incarnation of Christ.

Thomas was most likely introduced to Aristotle's writings at a very young age and realized that the ideas in those texts could help explain the thorny aspects of Christian doctrine. Thomas became wholly preoccupied with using Aristotle as a tool to build a model of the Christian worldview. When you read Theological Summa from the beginning, you can clearly see Thomas shifting contested Christian dogmas into his Aristotelian framework one after the other.

For example, Thomas explains the existence of God as a religious expression of the philosophical concept that a sequence of causes cannot be traced back indefinitely. Another example: in the Bible, God proclaims, "I am that I am." Thomas aligns this with the philosophical concept that posits not everything in the world can be fully explained. He also discusses the Holy Trinity, said to be one in essence, three in person: the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. Thomas uses the notion of categories developed by Aristotle to explain the unity of the Trinity. Similarly, he explains the duality of Jesus Christ, in whom coexist divine and human natures, by arguing that the primary substance, the divine person, assumes human nature, a secondary substance. Aquinas seems to delight in bringing up Aristotle again and again, like a child that has discovered a new toy.

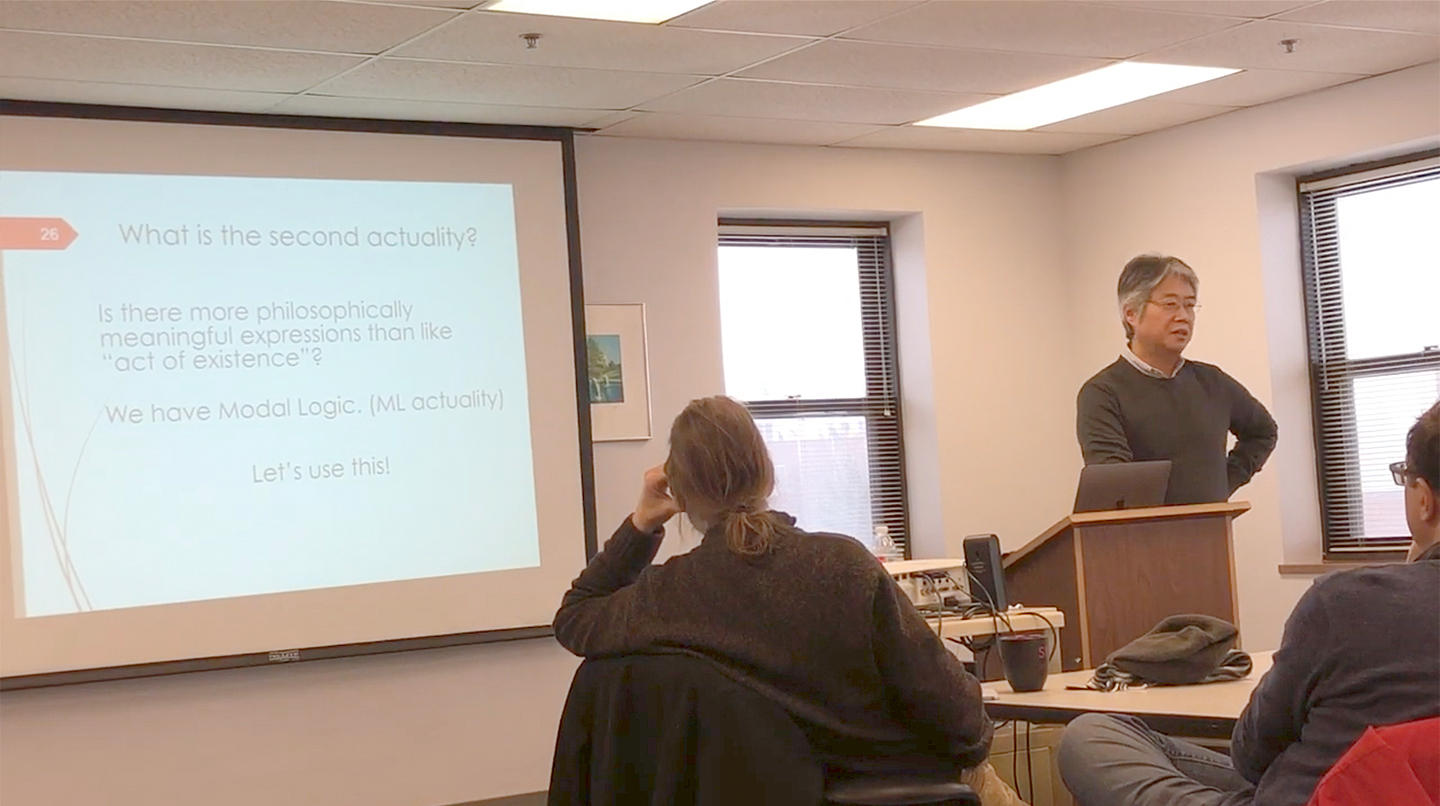

The ideas of Thomas Aquinas certainly include some highly problematic interpretations, especially when it comes to the meaning of "being" (esse). However, I like to believe that we can come to a more accurate and consistent analysis of his thoughts by focusing on his use of Aristotelian frameworks, especially his treatment of primary substances.

The second central theme of my research is modern British and American epistemology. A relatively new branch of philosophy, epistemology rests on the core assumption that knowledge is a justified true belief (JTB). Despite its short history, the field has received considerable acclaim and enjoys continuous development. One question that has fueled great controversy between epistemologists is how to overcome the Gettier problem, which argues that the aforementioned core assumption of knowledge as a justified true belief is false. Some philosophers have proposed adding conditions to this assumption, for example, that false beliefs should not be admitted or that evidence that is presented cannot be defeated. However, the controversy remains far from settled. Other epistemologists who stress the importance of external factors such as causation and reliability over internal factors such as evidence have begun to champion externalism in an attempt to profoundly change our understanding of knowledge. While this attempt seems to have had some success, it does not stand up as a theory because solid counterexamples have been raised to refute ideas of naive causation and reliabilism.

Today, epistemologists see the most promise in a theory called virtue epistemology. This theory incorporates internalist elements, such as evidentialism, alongside externalist elements like reliabilism. I find virtue epistemology very interesting and am following its evolution with a keen eye. At some distance from the developments that led from the Gettier problem to virtue epistemology, we also find the debate of contextualism. Considerations of the unique contextual dependence of knowledge are a fascinating part of the study of the nature of knowledge. Right now, I believe that knowledge comes from cognitive virtues that have the very practical goal of acquiring truths and facts, and that knowledge refers to the true beliefs described via those cognitive virtues. My current research focuses on developing a more detailed understanding of this process, primarily how these cognitive virtues are structured and how we can incorporate conditions such as safety into them.